The structure of math

Does math consist of arithmetic, algebra, and calculus, or is it more complicated?

Scott Alexander wrote a note speculating on effects of improved math education on students with different skill levels. With students who are bad at math, we can easily imagine that better math education could make them… well, better at math. But what about the students who are already very good at math?

If some fifth grader is way ahead and already learning algebra, it’s hard for me to imagine a slightly better teacher causing them to instead learn calculus, just because there seem to be diminishing returns - it takes an extreme amount of giftedness to get someone that far ahead.

This was one of those moments when I feel that I have the right qualification to state my strong opinions on the topic… but I am unable to compress them into a few lines. It took me a while to compose a reply, but I was not satisfied with the result. This post is my attempt to do it right, even if it takes hundreds of lines. And a few pictures.

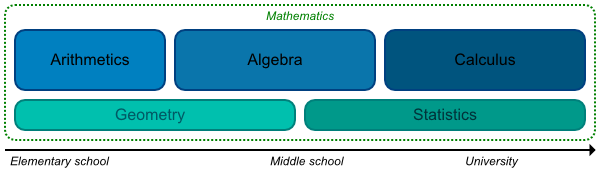

Most people learn math at school. It is only natural for them to associate the structure of math with the structure of school.

There is an elementary-school math, also called arithmetic. There is a middle-school math, also called algebra. There is a university math, also called calculus. The exact structure of math depends on the structure of school system in your country, in your era. (Wait, does it mean that different countries have different math? Don’t worry about that, most people are not familiar with how math is taught in other countries.) There are also some side topics, such as geometry or statistics, but those are mostly there to provide a short distraction from the increasingly complicated equations.

The elementary-school math is further divided to first-grade math, second-grade math, etc. Most people can’t tell you what specifically makes e.g. the fifth-grade math the right choice for the fifth grade of elementary school, but most of them would still be concerned if they heard that some school teaches some fifth-grade math topics in the third grade or in the seventh grade. Trust me, I read the internet.

This is not necessarily a model that smart people would endorse explicitly, if they thought about it for a while. But it is a model that comes up naturally, if they don’t.

It is also a natural conclusion if you assume that school is designed the way it is for a good reason. If 123×789 is taught in the fifth grade, there is a good reason for that. But there if a good reason for that, then 123×789 should be taught in the fifth grade.

Also, what is the alternative? Tell me, smart guy, when would you teach the fifth-grade math? — Sooner? Later? Not at all? — It is not obvious that any of these is better.

*

When I studied at university, I took lessons of educational psychology. We learned about the developmental stages defined by Jean Piaget. At the end of a lesson, the teacher concluded that there was a right age for each topic at school, and if you tried to teach it earlier, the children would not be ready to understand it.

That surprised me, because it was the opposite of my experience. As a child, I was a math prodigy, and I knew many things that were “inappropriate for my age”. And there were dozens of children like me. We did the Mathematical Olympiad, local correspondence seminars, and participated in summer camps for mathematically talented children. In the summer camps, university students volunteered to show us simplified versions of advanced math; I do not remember the exact year, but I think I was still at elementary school when I learned about derivations and Turing machines. Things that — according to my psychology teacher at university — should have been impossible for us to understand. And yet, I think we understood the gist of it.

So it felt like my existence itself contradicted the science. I tried to tell my class about it — there was even another classmate who had the same kind of experience — but the teacher and the rest of the class remained incredulous. As if we tried to convince them that we were aliens from another planet, and the laws of human psychology did not apply to us. From my perspective, they simply did not understand math. They understood “math, as taught at school”. But the actual math was… something different.

A natural objection could be that math prodigies simply learn math faster. But I don’t think that this was the whole story. Some of those summer camps were open to everyone — that is, everyone who agreed to spend half of their free time doing some form of math — and some of us also invited our friends, who were generally smart, but not math prodigies. And I believe that even those friends had a good time, and had no problem following much of the “age-inappropriate” math.

Which made me suspect that only a part of the story is about the mathematical talent, and the rest it simply about math being taught wrong at schools. This sounds more plausible when you find out that most math teachers are actually… not very good at math, to put it mildly… so the traditional math education at schools often consists of the blind leading the blind. And that professor of educational psychology… probably wasn’t good at math either. That should not surprise us, because people good at both mathematics and humanities are rare; people tend to specialize one way or the other. Talk about the psychology of math education, you need to have skills from both camps. Which is rare, even among the people with strong opinions on math education.

*

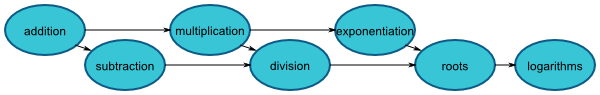

Let’s start with something specific and well-known, for example the arithmetical operators. There is addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, and later also exponentiation and root extraction and logarithms. If we tried to arrange them from the easiest to the most difficult, it would look like this.

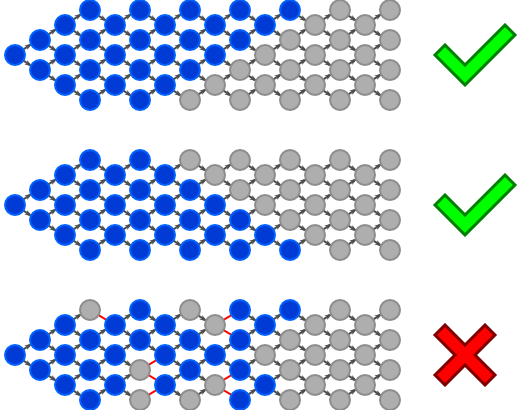

If you look at it closely, not all items in this sequence depend on the previous ones. Yes, multiplication is repeated addition, exponentiation is repeated multiplication; subtraction is the inverse of addition, division is the inverse of multiplication, and both roots and logarithms are inverses of exponentiation.

But there is no such relation between e.g. subtraction and multiplication. Neither of them seems to require the other, in principle. Is 3×3 more complicated than 9-5? We could teach either of those to a child who already knows addition.

(Teaching subtraction first is probably a better idea, but for a different reason. With multiplication, the numbers grow quickly. Knowing the numbers from 1 to 10, we can only do multiplication up to 2×5 and 3×3, but we can do lots of subtraction.)

Division can be taught as repeated subtraction; division with a remainder definitely contains the concept of subtraction. Calculating partial roots, such as √20 = 2√5, requires division. So perhaps the picture should be more like this?

I hope this picture conveys the idea of a structure that is ordered but not linear. You cannot teach math completely arbitrarily, but sometimes there is a choice. For example, you can easily explain the powers of 10 to a child who cannot divide by 3.

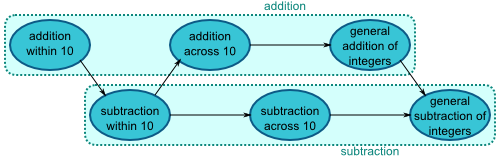

But the actual picture is way more complicated.

The first difficult thing in math, for many children (and their parents), is addition across 10. This is because addition across 10 inherently involves subtraction.

Notice what you are doing when you calculate e.g. 8+7. The first step is noticing that the result is going to be more than 10. Then you calculate how much remains between the first addend, 8, and ten. Ten minus eight equals two. Then you calculate how much remains from the second addend, 7, after removing the first intermediate result, two. Seven minus two equals five. Finally, you add ten and five, receiving 15.

In order to add two numbers whose sum exceeds 10, we have to subtract, twice.

Note: If you disagree with a specific arrow in the picture, that’s okay. I am not trying to get the exact structure of math right on the first attempt. I am trying to show the kind of approach and the level of detail necessary to get it right.

I don’t know if anyone has actually made a picture of entire math like this, even for the elementary-school math. But I imagine that good teachers of math use something like this intuitively. Perhaps not the entire graph at once, but if they think of a topic, they can reconstruct the surrounding nodes.

I used this a lot when I tutored children in math. People usually don’t look for a tutor immediately after they stop understanding something, but later, after the problems accumulate and the grades keep getting worse. So when they tell you they don’t understand something, you can’t simply start explaining the topic — they probably don’t understand the prerequisites either. You need to think of the topics preceding this one, and check their knowledge of those. (Don’t just ask. Give them a simple problem to solve.) If they fail, backtrack further, until you find the original point of confusion. Then, rebuild the knowledge.

For example, they may ask for help solving quadratic equations, but the underlying problem is that they don’t know how to multiply expressions in brackets, so they can’t figure out the mystery of (a - b)². Or they may ask for help reducing fractions, but the underlying problem is that they have no idea what fractions are, i.e that they might be somehow related to division.

If you are planning lessons, or writing a math textbook, you need to flatten a part of this graph into a sequence. Time is linear, and so are books.

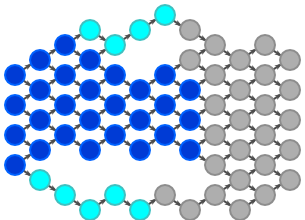

But I can imagine a computer system for teaching mathematics, which would show you the individual pieces of knowledge as nodes, with different colors for those you have already learned, those you are ready to learn right now, and those where you still need to learn some prerequisites. I think this would be amazing, because it would allow each student to learn not only at their natural speed, but also following their natural curiosity. Different students could choose different goals, and get highlighted the nodes contributing towards that goal. No more “but why do I need to learn this?”

(In a perfect world, all knowledge of humanity would be organized like this, and freely available for everyone, at any time.)

*

We have arrived at the mystical sounding knowledge: To teach addition, you first need to understand that (from the perspective of a teacher) there is no such thing as addition. There are only various concepts and skills related to the idea of “addition”. Each of those concepts and skills needs to be taught as a part of a larger structure; and they are sometimes intertwined with things that are not obviously parts of “addition”.

addition within 10

addition across 10

multi-digit addition

adding a zero does not matter: a + 0 = a

the order of addends does not matter: a + b = b + a

parentheses between the addends do not matter: a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c

These all are just parts of adding natural numbers. (You can also add decimal numbers, fractions, complex numbers, vectors, matrices, infinities, etc.)

Even the concept of a “natural number” is more complex than it seems, and interwoven with other concepts:

Numbers from one to ten are memorized, like a poem. Sometimes an actual poem or song is used to make it easier.

Zero is a special number; it requires more abstract thinking.

Numbers from thirteen to nineteen imply addition: thirteen is three plus ten, fourteen is four plus ten, etc. Even the numbers eleven and twelve are etymologically “one left (over ten)” and “two left (over ten)”, although a typical English speaker probably just memorizes them.

Number from twenty to ninety imply multiplication: twenty is twice ten, thirty is three times ten, etc.

Numbers one hundred, one thousand, one million, imply powers of ten.

So these deserve separated nodes in the structure of math.

By the way, between the concept of a (natural) number and the concept of addition, there is a concept of a successor and a predecessor; they are much easier than addition and subtraction in general. Between addition (within 10) and subtraction (within 10), there is the “five plus how much is eight?” intermediate step: technically subtraction, but expressed using the language of addition.

Is it really necessary to get into this level of detail? For most people, no. For teachers (in general, not just math), this is a skill that seemingly gives them super-powers. You can get a lot of value from the following algorithm:

think about something that you want to teach or train

try to split it into smaller parts, or multiple smaller steps

try to split those parts/steps into yet smaller parts/steps

again

again

again

teach/train all those little parts/steps separately

then gradually put them together

When executed well, the result is a shocked student saying: “But that was so easy! And everyone kept telling me how hard this topic/skill was.”1

Take a student who has a problem with addition across 10. Now instead of numbers or fingers, let them use a number line. Let them calculate 8+7 by starting at number 8, and taking 7 steps to the right. There, 15. Keep doing that, but draw their attention to the moment when they pass 10. “One, two (we are passing ten), three, four, five, six, seven (done).” Later start with asking “how much until we pass ten?” and “how much will then remain?”. When the student can answer these, they no longer need the line.

*

I don’t know what the actual structure of math looks like. The graph is too large, too complex, and I don’t even know most of its parts. Perhaps no one does.

So I will just draw a random small graph, and use it as a metaphor for the real thing.

What is at the beginning?

The elementary-school math starts with things like counting “one, two, three” and telling the difference between a straight line and a zigzag line. (Or perhaps they already do it in kindergarten.) Are these the fundamental atoms of human thinking?

Not really, but the previous steps are things that we no longer recognize as “math”. Before counting, there is the experience of having multiple similar objects. Before classifying lines, there is the experience of touching objects: straight, round, angular.

Does math split into multiple branches, or is it all connected?

At first sight, sure it splits: arithmetic vs geometry; number theory vs analysis; graph theory; logic; topology… On the other hand, you can express geometrical shapes using equations; some proofs about prime numbers involve logarithms and number π…

Are these connections between seemingly unrelated branches of math random and rare, or does it seems like everything is somehow connected to everything once you have learned enough? I have no idea; ask Terence Tao.

Where does it end?

No idea again. Maybe it never ends, it just gradually gets too complicated for any human to understand? Or maybe there is a large but limited number of fundamentally different concepts, and the rest is “more complex versions of essentially the same”?

But I think that for all practical purposes, you learn math until one day you stop, or you die, and at the end you have learned many interesting things, but there wasn’t a single specific final equation or final insight that somehow wrapped it all up.

And even if school tries to have some final goal, e.g. teach you calculus, there will still be some unrelated things, such as statistics, or how to construct a triangle.

*

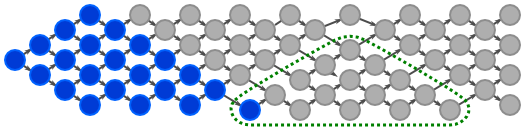

Seeing the structure of math as a graph, as opposed to a line, allows us to propose educational strategies more sophisticated than “advance slowly” and “advance fast”.

First, we can see how different teachers, or different schools, could teach mathematics in different order. As long as they follow the inner structure of math, that is, always teach the prerequisites first, it will work.

So instead of teaching everyone the same things, we could choose the educational goals that we want to achieve, add the prerequisites, and their prerequisites, etc., and we have the curriculum. Which can be taught in any order that follows the structure.

Some things are so early in the structure, that they will probably be necessary for everyone, such as addition. Some things later in the structure will be optional, for example quadratic equations.

Sometimes you have mathematically talented students in your classroom. If the entire classroom is talented, you can teach them math faster. But more likely you have an average classroom with only one or two mathematically talented students. Teaching them faster would mean that from now on you have to teach them everything separately until the end of school.

Another solution is to teach them something extra — something that is not in the curriculum for the average students. So they can both learn something more, and also learn together with their classmates at the beginning of the next topic.

For example, after teaching children addition, it is a convenient moment to talk about money. There are coins and banknotes of certain value, such as 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, etc. Any amount you want to pay, you need to put together out of these. (For the moment, let’s ignore the fact than in an actual shop you could get some change back, or use a card. Let’s also ignore euros/cents.)

How would you pay 3, or 4, or 6, or 7? Let’s write down the numbers from 1 to 20, and for each number find out how would you pay it. If children notice that sometimes there are multiple solutions, encourage them to use the smallest number of coins.

So far, we are technically doing addition (of more than two numbers). Finding the smallest number of coins was trivial; we just needed to always use the largest possible coin.

But for the mathematically gifted students, you can give an extra task, using different coins. What about 1, 3, 4? (Currency of a fictional kingdom.) This time, choosing the largest possible coin is not the right move if you try to pay 6.

What if we do not have a 1 coin? Let’s only keep the 3 and 4 coins. Some amounts cannot be paid, for example 1 or 2. What is the largest amount that you cannot pay? What is the smallest amount that you can pay in two different ways? Write down the numbers from 1 to 20, and find out how would you pay them, using the smallest number of coins. Is there a pattern?

What happens if we only have coins 4 and 6?

Imagine a magical kingdom that uses the following coins: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64… the next one is always twice as much as the previous one. Write down the numbers from 1 to 20, and use the smallest number of coins to pay them. You may notice that we never need to use the same coin twice. Why?

These exercises no longer feel like the usual school math, right? Addition is work. But this feels more like exploration. (Especially when I don’t tell you the right answer.) And because these problems are outside of curriculum, there are no time limits, and no tests. The only thing pushing you forward is curiosity. This is what mathematics should feel like.

You may wonder whether such detours are a waste of time, from the perspective of the officially approved curriculum. Maybe yes — but if you enjoy math, it is still time pleasantly spent. Maybe no — you may notice that the last exercise was practically an introduction to binary numbers… but in a way accessible for a (gifted) first grader.

Let’s return to the original question. If a smart fifth grader already knows algebra, what else is there to learn, besides calculus?

Now we know that “algebra” and “calculus” are not nodes in the structure of math. They are collections of nodes. Some of those nodes are earlier in the graph, some of them are much later. Many are outside the usual school curriculum; some of them because they are too difficult, but many because there is simply too much potential stuff to learn, and not enough time for everything.

Solving 2+x = 7 is algebra. Proving that (a+b+c)/3 ≥ ∛(abc) for a,b,c ≥ 0 is also algebra.

Integrating a polynomial is calculus. Integrating… something else… is also calculus.

The most difficult parts of algebra are more difficult than the easiest parts of calculus. A hypothetical student smart enough to know all of algebra would have no problem learning the easy parts of calculus. A student who knows all high-school algebra could use the extra math lessons to learn the parts of algebra outside the curriculum.

This is another fun thing you can do with mathematically talented kids. Find a part of mathematics that is famous for being advanced — and choose a subset that is actually quite simple. Teach that simple part, and stop there. The kids will have fun, and it will encourage them to explore the topic later.

Most people would probably agree that multiplication is more difficult than addition; division is more difficult than multiplication; and fractions are more difficult than division. And yet, I think that many 6 years old children would be able to solve the following problem: “If Adam has 2 and ½ apples, and Betty has 1 and ½ apples, how many apples do they have together?” That’s because fractions in general are difficult, but the specific fraction ½ is not, especially if all we do is add it to another ½.

Wrapping it up:

To design a mathematical curriculum, we need to work with details smaller than e.g. “arithmetic” and “algebra”; even smaller than e.g. “addition” and “subtraction”. We need to see how these details are connected to each other.

No teacher remembers the entire graph of math, but if you tell them a specific topic, they should be able to tell you the topics right before it, and some topics right after it.

There are too many things in math, and we only teach some of them at schools. Not because the rest is too complicated, but simply because there is too much math, and not enough time. That means that if you want to enrich the curriculum, you do not need to add more difficult things; you can also choose things that are usually left out.

(Things that are left out may include unusual applications of the usual things, such as doing addition using coins, and wondering about the effects of having different coins; or entire areas of math, such as binary numbers, or complex numbers.)

Many advanced areas of math contain parts that are simple. You don’t have to teach everything at once. Feel free to give children a cherry-picked preview.

If we created a perfect educational environment, where:

each child can learn at their individual speed

all knowledge is available, and explained by a competent textbook/teacher/AI

there is advice “given the things you already know, this is what you can learn next”

the children are motivated to learn things

…I believe that all children would benefit, but the mathematically talented children would probably benefit more, i.e. the achievement gaps would grow.

That’s because the mathematically talented children are typically not bottlenecked by their biological age (they don’t already know everything that is biologically possible for an N years old child to know), but by the lack of good educational resources, and by the lack of guidance (they don’t know about some things that they could easily learn).2

I believe that the results we get now, even at the best schools, are still very far from what is possible. We are not anywhere near the ceiling yet.

The opposite of this approach is concluding that some students are just hopeless, and writing an article about how “the camel has two humps”, only to retract it later.

I am not saying that all students are equally able, or that you can teach anyone anything. But nature usually follows a normal curve; and between “can learn it” and “can’t learn it” there is usually an intermediate step “could learn it, but it would take an insane amount of time”.

If instead you get a specific step where some students fail completely, and others pass it easily, that is precisely the step that needs to be split into smaller parts.

And maybe there is not enough time for that, so you just have to take the students who get it, and send everyone else home. That’s fair. But that doesn’t say anything about innate human ability to master the task. It just means that your course is an intermediate course; and perhaps someone else should also make a beginners course. (That’s basically what tutoring means — creating an individualized beginners course for the failing student.)

By good educational resources I mean books / videos / interactive lessons that would explain the topic in the easiest way possible. It seems to me that often, once we find a way to teach something, we stop looking for easier ways to teach the same thing.

I blame this on the dual role of school, as an institution both for teaching and for certifying students. Once you accept that it is okay, even inevitable, for some students to fail, then as long as some students succeed, it feels like you are doing your job well. If you grade on a curve, it does not even matter whether you teach well or not, the numbers are the same.

By good guidance, I imagine someone knowing the structure of math, and recommending good educational resources for every topic.

Note to subscribers: Don't worry, there will be more articles on programming games in Java.

It's just that sometimes I also have other topics I want to write about, and given my low frequency of writing, I don't want to create yet another blog, which would contain maybe one post per year.